In Sweden, there are several types and styles of wooden chests and boxes.

The distinction between the two is somewhat vague; according to Norstedt’s Swedish encyclopedia (1990), a chest is a large, box-like piece of storage furniture with a lid, of an older type, nowadays having a mainly ornamental function. A box is a small, well-made lockable container, with a lid, for storing a particular type of object.

Viking-era chests and boxes

The Oseberg ship was discovered and excavated in the early 1900s in Vestfold, Norway. The ship was built in the first half of the 9th century. Many items were found on board – including storage chests. Chests were generally used by the crews of the Viking ships, who sat on them to row, as well as storing things in them.

In 1936, a wooden tool chest was discovered during the plowing of a field at Mästermyr on Gotland. Over two hundred iron objects were found inside and around the chest, which is 90 cm long and 24 cm high. Of particular interest in the present context is the fact that these objects included blacksmith tools as well as two large keys, lock parts, other lock hardware and three small padlocks.

A hundred years ago, archeologists found some Viking-era keys in the area around Värnamo in Jönköping County. The keys, which were made of iron, were identical in appearance. Since no lock parts were involved in this discovery, the author has created a reconstruction of a chest with a lockable lid, all in wood.

|

| Reconstruction of a Viking-era chest. Photo by the author. |

|

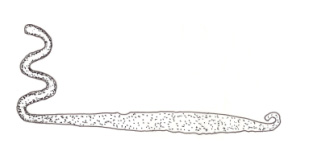

| Sliding bolt lock key from the parish of Lanna in Jönköping County. Sketch by the author. |

The chest is fitted with a sliding bolt lock. The purpose of the key is to lift and shift a wooden bolt to the side in either direction, into an open or closed position. The keys are found in only two sizes – a large one for chests and doors (approximately 18 cm in length) and a small one for chests and boxes (approximately 11 cm). The shafts are narrow, with a small loop at the top for a chain or ribbon, and have the characteristic S bit at the bottom.

This simple mechanism is based on earlier lock principles developed elsewhere in Europe by Romans and Celts.

|

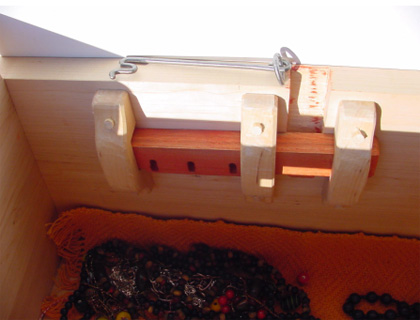

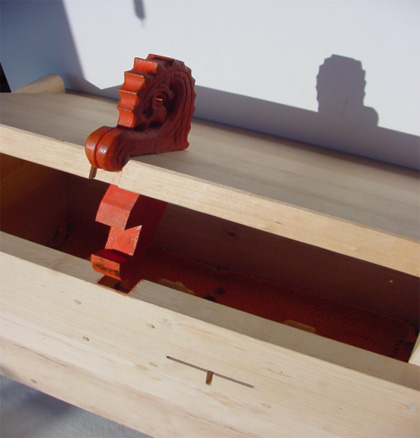

| Sliding bolt lock on a Viking-era chest (with key). Reconstruction and photo by the author. |

A wooden bolt slides horizontally in double wooden or metal brackets on the inside of the chest. A corresponding bracket is attached to the front edge of the lid. The key is inserted through a slot in the front of the chest and then into a notch on the bolt. It is then a simple matter to shift the bolt sideways to lock the bracket of the lid in place or release it.

|

| Sliding bolt lock on a Viking-era chest (with keyhole). Reconstruction and photo by the author. |

Further examples of locking devices for Viking-era chests.

|

|

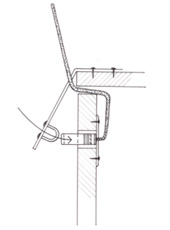

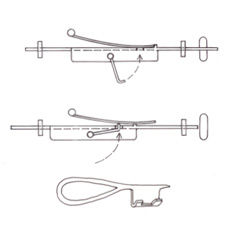

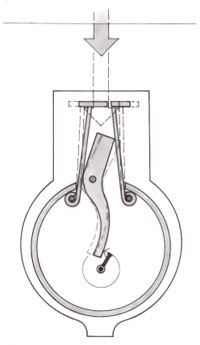

| The key depresses the spring and shifts the bolt. Sketch by the author. |

The claws of the key depress the spring and shift the bolt. Sketch by the author. |

|

|

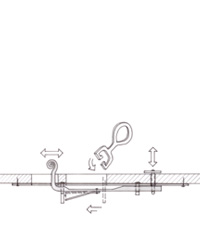

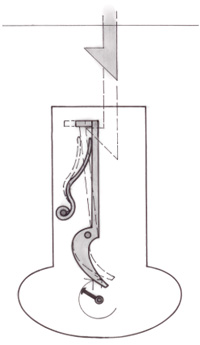

| The key presses together the springs and the bolt can be shifted to the side to release the staple. Sketch by the author |

Side view of the lock. Sketch by the author. |

|

|

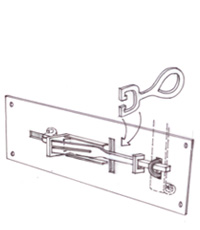

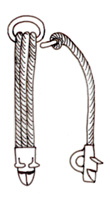

| Bronze hasp and staple with meshed bronze wires. Sketch by the author. |

Viking-era chest with hasps and staples.Sketch by the author |

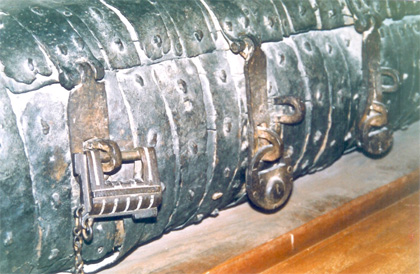

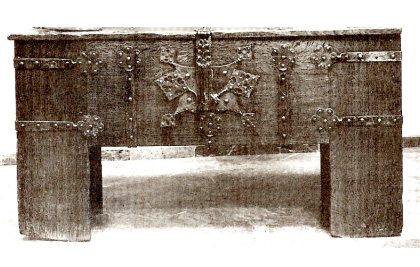

Dugout chests

The Museum of National Antiquities in Stockholm contains a chest made of a hollowed-out log, to which a lid has been attached. It is from the Övergran Church in the district of Håbo in Uppland, where it served as a money chest. The entire length of the chest is clad with vertical forged-iron strips nailed down all around – as is the lid, to which are attached four iron hasps, each fastened to the strip on the lid by a hinge. At the other end of each hasp is a hole for a staple that is attached to the chest. Locking is achieved, as shown by the following illustration, with a padlock, the bolt of which is passed through the staple. Such dugout chests were used throughout the Middle Ages from the twelfth century on, and the lids were locked down with padlocks.

|

| Iron-bound dugout chest from the Övergran Church in Uppland. Swedish Museum of National Antiquities in Stockholm. Photo by the author. |

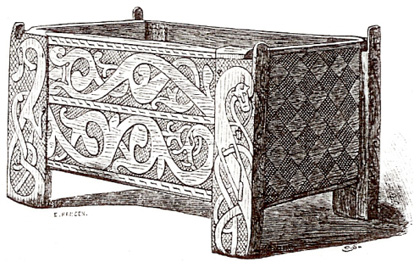

Stile chests

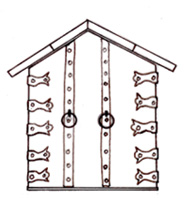

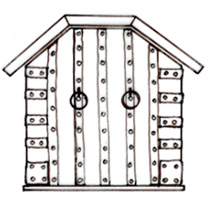

Stile chests are more common than dugout chests. They are constructed with stiles in each corner, which also serve as legs. This is an old furniture concept that originated in the classical cultures and was brought to Sweden by missionaries in the twelfth century. Stile chests are often decorated with fine carving. The lids were secured with by hasp, staple and padlock, or drop fork lock. Ornamentation sometimes took the form of chip carving.

|

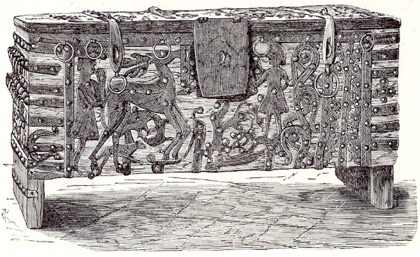

Beautiful ironbound chest from Voxtorp Church in Småland, from approximately 1200, built in the Viking manner. It is meant to be secured with three padlocks.

Figure: Kyrkliga konsten under Sveriges medeltid. Hans Hildebrand, 1907. Nowadays the chest is kept together with two similar chests from the same county, in Swedish Museum of National Antiquities in Stockholm. |

|

Military trunk, a stile-type trunk, from Västergötland.

Figure: Evald Hansen. Hans Hildebrand’s Sveriges medeltid. Kulturhistorisk skildring 1–3. 1879–1903. |

The Gothic period

During this period, chests had flat lids or lids resembling a gambrel roof or pitched roof.

|

| Gothic chest with flat lid and drop fork lock. Photo by the author. |

|

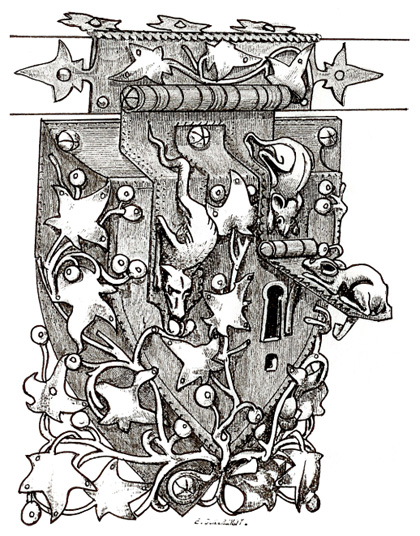

| Gothic double drop fork lock. The keyholes are guarded by two mice and a dragon. Dictionnaire du Mobilier Francais. E. E. Viollet-le-Duc, 1809 |

|

|

| The gable of a medieval chest with a pitched roof-type lid. Sketch by the author |

The gable of a medieval chest with a gambrel roof-type lid. Sketch by the author. |

Chests from the Vasa renaissance

In the 16th century, the more roughly hewn chests were replaced by ornately carved ones. Various types of joints and wood materials afforded chests a new look. Beginning in this period, chest makers began recessing the joints – joining the sides with dovetail-shaped pins (dovetailing) and using arched lids. At the same time, many older tall chests were rebuilt and upgraded into cupboards.

Chests were kept in the occupied rooms of the house, the trunk room or the attic. In many places there were special sheds for storage chests.

The new furniture chests were also fitted with new types of locks, imported ready-made from southern Germany or manufactured on site by invited locksmiths.

|

| Chest maker, 16th century. |

|

| The Holy Family: the flight to Egypt. The chest was an integral element of the furnishings of a typical home. Figure: Niels Hemmingsen’s postil, 1576. |

|

| Chest locks of a southern German type made in the middle of the 16th century. Photo by Pierre Rosberg, Kalmar County Museum. |

|

|

| Chest lock with circular spring. Sketch by the author |

Chest lock with single spring. Sketch by the author. |

The Baroque period, the Enlightenment and the 19th century

County roads

In the 17th century, as transportation developed, giving rise to the mail stagecoach, the need arose for a traveler’s chest or trunk that would be suitable for the vehicle in question and the length and purpose of the journey.

|

| 17th-century stagecoach. Figure: E. Dahlberg, Suecia antiqua. |

|

17th-century traveler’s chest. The lock is located on the short end of the chest.

Figure: Troels-Lund, Dagligt liv i Norden, 1945. |

At sea

The rise of commercial seafaring in the 17th century, expeditions to “New Sweden” on the Delaware River in North America, and in the 18th century to Canton in China, meant year-long voyages with crews demanding more and more comfort. The advent of the seaman’s chest enabled both officers and crewmembers to keep their personal belongings well protected. Pharmaceutical preparations and medicaments were transported in their own specially made chest.

|

| Seaman’s chest in the Gothenburg Marine Museum. Photo by the author |

|

| Medicine chest in the Gothenburg Marine Museum. Photo by the author |

At home

In the 18th century, chests were decorated with rococo floral painting, traditional Swedish country-style painting, marbling and masur birch veneer.

Bridal trunks were marked with monograms and significant dates. The bride’s trunk or chest was not merely a box in which to pack her trousseau, but was often painted and carved, and was sometimes also a painted showpiece to adorn the wall of the largest room. In wealthy situations, there might be several chests involved.

As with cupboards and other furniture, carpenters began to attach spherical or four-sided feet to chests.

Chests owned by country folk were fitted with locks that had a circular spring either recessed or placed on the inside at the upper edge of the trunk with the corresponding arrow-shaped hook attached to the lid.

Tumbler locks were also used as chest locks – on the lids of iron/steel chests or on the front edge of a wooden one.

19th-century trunk locks

In the late 19th century, chests were moved out into the sheds. The large carved and painted wall cupboards and armoires were much more practical. During the 20th century, for various reasons, the old trunks once again became sought after, and migrated back into the home. Since then, decorative rustic furniture has been trendy and fashionable.

The people who emigrated from Sweden in the latter half of the 19th century packed their belongings in sturdy wooden chests and hid the keys in their clothes.

Examples of 19th-century trunks with a drop fork.

|

|

| Trunk lock. Photo by the author. |

Aluminum trunk. Photo by the author. |

|

| Wooden trunk with reinforcements of sheet iron and brass-plated sheet iron. Photo by the author. |

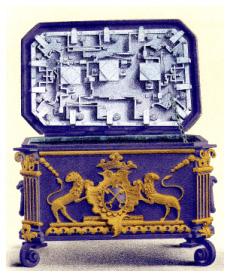

Guild chests

The large silver “Welcome” plaque had its place in the craftsmen's trunk – the guild trunk – which held the guild charter and the ceremonial vessels of the guild.

|

| Trunk of the Stockholm blacksmiths’ guild. Photo from the author’s collection. |

Iron money chests

The oldest preserved money chests, which are from the early medieval period, are made of wood – oak or pine – and have strong iron fittings. The chest from Voxtorp (see above) is a money chest, as well as a unique example of Roman metalworking art.

The churches’ money chests and collection chests usually had iron fittings, too, although without being decorated. An example of this type of chest is found in the Övergran Church in Uppland (see above).

In the late medieval period, chest makers switched over to making chests entirely of iron, with or without strip-iron reinforcements. Particularly high-quality cash boxes and money chests were made in southern Germany, as well as in France. They might feature ornamentation, chasing, etching, gilding, brass detailing, etc. The locking devices were recessed into the lids with a large number of bolts that could be opened in four directions and closed with a single key. In addition to the lid lock, the chest could be protected with locks on the exterior surface including drop forks or clamps that could be secured with strong padlocks. Wooden money chests with iron fittings continued to be used concurrently, however, particularly in church sacristies. Locking of chests using only a padlock also occurred.

|

| Money chest for the collection in the Mariekirche in Lubeck, Germany. 16th century, with two padlocks from the same period and lock bolts built into the lid that were controlled with the key from the front. Photo by the author. |

In the event of fire, iron money chests provided no protection for securities, bank notes and the like, when they became hot. Consequently, there was an urgent need to try to find a room that would be safe from both fire and lock-picking.

More on the secure storage of valuable items can be found in the article entitled Safes and vaults in the Web book.