Design

Britain

Most likely, British engineer William Marr designed the first modern-style fireproof safe. His patent is dated as early as 1834. What was new about Marr’s safe was the idea of using double walls of steel with heat insulation between them. The ideal insulating materials presented a technical challenge; Marr used finely crushed marble, with clay and porcelain to bind it.

Another contemporary inventor, Thomas Milner from Sheffield, achieved even better insulation by using alum and other alkaline salts to create an insulating layer of steam when the safe was heated.

The beautifully painted steel cabinets also required unpickable locks. A large number of British and American inventions of tumbler, combination, code and time locks from around this time helped protect their contents.

The first World Fair (called the Great Exhibition) took place in London in 1851, and a special Crystal Palace was built in Hyde Park to host it. Alongside all the key achievements of the world’s industries to date, the exhibition demonstrated several models of safes from various manufactures from around Europe.

|

| The Crystal Palace 1851, London. Sketch by the author. |

Sweden

In the mid-19th century, industry and trade had begun to thrive in Sweden as well. Banks and companies began to see the value of using safes, as did merchants, wholesalers, traders and manufacturers. In addition, foundry owners, industrialists and factory proprietors hid their documents and cash in a locked, safe place.

Besides safes, people also began using armored or in some other way reinforced doors on their vaults or similar storage facilities, and locked valuables cabinets.

Rosengrens safes

Rosengrens in Göteborg has been manufacturing safes since the mid-19th century. Most likely their original models were copied from imported British high-security safes.

|

|

| EA Rosengren (right) and J Rasmussen in the late 19th century. |

Still fire and burglar proof over 100 years later. |

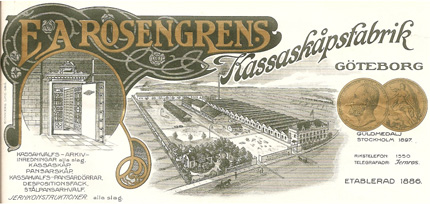

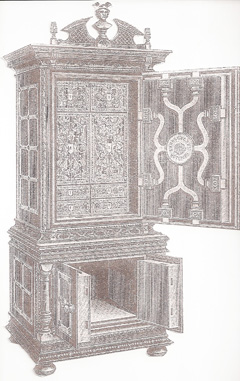

Smith Peter Rasmussen started his business in 1847. Over time it grew to a whole smithing workshop with a wide range of products, including locks and even safes. Then 20-year old locksmith Edvin Albert Rosengren bought the smithy in 1886. Eleven years later he received a gold medal bearing the image of the king during the World Fair in Stockholm for an extremely decorative and effective safe. EA Rosengren proudly displays both sides of the medallion in the vignette below.

|

| Vignette on the company’s reference list, dated 1907. |

Rosengren was a social person, an industrialist with a good head for business. EA Rosengrens Kassaskåpsfabrik (Safe Factory), as it was originally called, grew very rapidly and added on new products, such as safe-deposit boxes, vault doors and heavy valuables cabinets. In the early 20th century, EA Rosengren set his sights on the export market, delivering safe-deposit boxes and vault doors to neighboring countries and Russia. He built his first industrial facilities on the island of Hisingen off the coast of Göteborg in 1905.

|

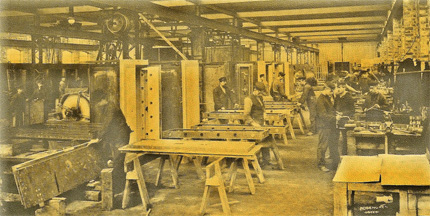

| Rosengrens in Göteborg. Manufacture of vault doors in the early 20th century. |

Since the outset, Rosengrens has been Sweden’s leading supplier of safes. The company’s 1907 reference list shows that in the previous year the company had delivered materials for the construction of the Riksbank, the National Bank of Sweden, in Stockholm: 18 armored doors and armored windows, 2 vault doors, barred walls, gates, 37 vault cabinets, 5 double-door safes, 700 meters of shelving, key cabinets and more. But this was just one of several hundred orders in the years 1898–1907.

Buyers also included the National Debt Office, the Swedish Royal Post Office, the Swedish Royal Army Administration, banks, hotels, manufacturing industries, insurance companies, the Dalsland Canal Company, the town of Billingfors, railroads, butcheries, weaving mills, the Swedish Steel Producers’ Association, the City of Stockholm, city planning offices, courthouses, courts, county councils, the Persberg Mining Company, stockbrokers, gasworks, transit companies, breweries, and L M Ericsson. The company also exported to Russia and what was then Russian Finland, as well as to Norway and Denmark.

There is a true story about the company’s delivery of safe-deposit boxes to Russia, to the Second Mutual Credit Company in what was then called Leningrad. The story is told by Gustaf Sjölander, inventor and chief engineer at the company. During the tendering process, giant companies from Britain, France and elsewhere, and little Rosengrens from Göteborg, were asked to exhibit their works. When explaining the technological advantages of their products to the board, they were asked, “Of course you consider your products to be the best, but which company do you feel has the next best products of all the assembled tenderers?” Considering the size of the unknown Rosengrens, everyone decided that there was little risk of them being selected, so they named Rosengrens as next best after themselves. That was how Rosengrens got the order – they got everyone’s vote.

After Rosengren passed away in 1910, the company re-formed into a corporation. In 1931, EA Rosengrens was the first company in the country to officially fire-test safes. In 1912, Gustaf Sjölander patented his mutator lock, and the year after his “lessee lock” for safe-deposit boxes, which consists of a lock with interchangeable cores containing the disc tumblers. The tumblers had no springs and were manipulated solely by the key. It was easy to switch lock cores, making them perfect for safes, safe-deposit boxes and post office boxes.

|

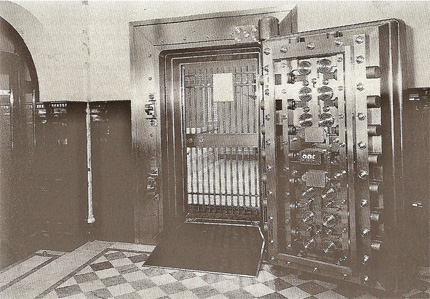

| Vault door, delivered from Rosengrens to a bank in Stockholm in 1910. |

After the Second World War, Rosengrens’ manufacturing was streamlined with new types of machines.

In 1945 the company designed the mechanical combination lock (CNAB). In 1958 they were again first to officially test safes, this time against burglary (lock picking). The combination lock settings were even checked by X-ray to ensure that the method did not work.

In the late 1950s, Rosengrens became a part of Coronaverken AB, a washing machine manufacturer. Later, in 1965, Coronaverken bought a company in Malung that took over Rosengrens’ manufacturing from Göteborg and remained the company’s manufacturing base until just a few years ago.

Another landmark came in 1963, when Rosengrens manufactured the first resettable key lock (ABN).

Starting in 1972, Göteborg once again became home to Rosengrens’ administrative, development and design departments. Among their products in the mid 70s were complete ranges for banks including vault doors, vault gates, safe-deposit boxes, cashier cabinets, service boxes, valuables cabinets, fireproof document cabinets and fireproof vertical cabinets.

Vault doors came in several versions – from simple ones for industrial storage of valuables to the giant 300 door for bank vaults.

|

|

| Rosengrens’ 300-type bank vault door |

Customer lock cores with eight tumblers for bank boxes, etc. Photo by the author. |

Strongroom doors were designed so that you had to go through manholes if you wanted to force your way through. Targeting specific vital parts of the door automatically triggered bolt jams. At the front of the door was a 100 mm thick sheet of steel, the whole surface in front of the lock mechanism was secured and the keyway shafts were reinforced with grains of carborundum to make them drill-proof. Most of the doors were covered on the inside of the front sheet-metal wall with a 2-circuit alarm tape for connection to the alarm system.

In 1974, Coronaverken was sold to AGA, and in 1987 it was sold again to Kullenbergs förvaltnings AB. In 2006 the company name EA Rosengrens AB was changed to Gunnebo Nordic AB.

Now, in 2008, some manufacturing takes place in Mora while other parts of it have been outsourced to countries such as France, the Netherlands and Indonesia. Above all, the Mora plant makes fire-safe document cabinets for computer media, burglarproof and fireproof document cabinets, burglarproof cabinets, storage cabinets and safe-deposit boxes. The locks are purchased from ASSA AB, and quality is assured through internationally approved product tests. A test shows that that specific product is fireproof. The test certificate shows that the product has passed a test, that it was performed by a certified laboratory and that the other products are identical to the tested one. A range of standard tests and testing methods are used worldwide. The most common ones are the European EN 1047-1 and NT Fire 017, the American UL 72, and the Asian JIS 1037 and KS. The EN test consists of two separate tests, one for fire resistance and one for resistance to heavy impacts and falls of up to 9.5 meters into a bed of gravel. The safes are heated to an internal temperature of 170 degrees C for the fire test, and in the fall test they are heated red-hot.

|

|

| Rosengrens’ safes received a medal in the 1897 World Fair in Stockholm |

Other safe manufacturers

Hagelins Kassaskåpsfabrik, founded in 1857, was briefly owned by Rosengrens in 1980–90, and was then sold to Tann Värdeskydd AB in Gävle. In the 1930s, AB Carl Särenholm in Eskilstuna manufactured safes. The company was founded in 1895 and became incorporated in 1934 with a share capital of SEK 360,000 and a staff of 125. Hadak Security AB began manufacturing safes in 1944 in Eskilstuna and Mora. Rosengrens acquired this company in 1988. Jöli has made safes in Sweden since 1950. Ving Card/Elsafe in the ASSA group now makes safe-deposit boxes for hotels and other contexts.

|

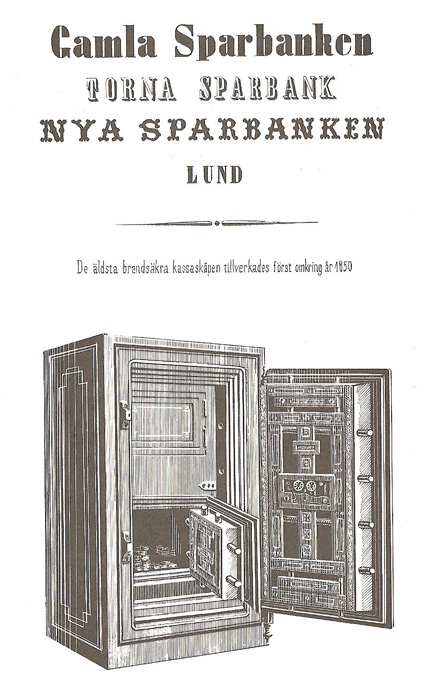

| Ad from the early 20th century in Lund. |

Safes

The task of a safe is to store valuables with a personal or financial value. Modern safes come in a variety of wall thicknesses and brands, with a wide range of lock types. Many people purchase safes or valuables cabinets for personal use, and most workplaces now have access to some kind of fire and theft-proof document storage.

In its most simple form, a safe consists of double steel walls insulated with a fireproof lining, and steel doors with built-in bolts and some kind of combination lock.

Locks on safes

There are many ways of trying to crack a safe; its age and design determine how successful the attempt will be. Regardless of age, the easiest way to crack a safe without damaging it is to jimmy the lock. Some older safes have rotating combination locks that can be manipulated by feel or sound to find the combination. Various mechanisms in the lock are designed to make it harder for thieves to break the code. Modern, more sophisticated locks use soft, light materials to reduce this vulnerability.

Another anti-manipulation mechanism is serrated wheels (false tumbler notches) that make tactile techniques much more difficult. There is also a type of driver wheel that prevents contact of the fence to the tumblers except in one position. These locks can be identified by clicking in the dial.

A safe cannot be any more secure than its combination. The easiest way to obtain the combination is to steal it. Surprisingly often, safe-crackers have been able to simply guess the combination – whether by skill or luck. This may be because the buyer has not changed the standard manufacturer-set combination, or because owners often use easy-to-guess combinations such as birthdates and the names of loved ones.

Safe-cracking

Safe-crackers usually work at night, between 1 and 4 am. They arrive at the crime scene in a transport vehicle and disable the alarm system. Thieves often enter through a window, door, outer wall or through the ceiling. Once inside, they may have to cut through an interior wall. In most cases, they simply load the safe into their truck to open it at their leisure somewhere else. Fire alarms keep them from cutting into the safe on site.

Forcing open a safe door

When the owner of a safe has lost the code or combination, there are several methods of breaking into the safe. Locksmiths will try to pick the lock manually to avoid causing damage and the need for repairs. The challenge to the locksmith and the time it takes to pick these locks has increased as lock systems have become more secure.

Another method is to take advantages of weaknesses in the lock system. Most safes are susceptible to compromise by drilling or other physical methods. Manufacturers publish drill-point diagrams for specific models of safe, which are carefully guarded. Drilling is the most common method used by locksmiths and thieves alike. By positioning the borehole just right, they can examine the condition of the combination lock while manipulating the lock gates so that the fence falls and the bolt is disengaged. Drilling in hardplate steel requires special equipment and is very time-consuming. In addition, modern safe doors are protected by mechanisms that react to drilling and heat, and trigger additional bolts built into the door. For locksmiths, drilling is a faster method than picking the lock. Drilled safes can generally be repaired and returned to service.

Modern safes are fitted with a “relocker” that reacts to violence committed on the safe and triggers additional bolts. Once a relocker has been triggered, the lock must be picked, as neither the code nor the key will work.

Forcing through the walls of a safe

Another way to break into a safe is using explosives.

The side walls of a safe are easiest to destroy. Various types of blowtorches can be used to cut the metal. A modern type is the plasma cutter, which melts or vaporizes the material with a high-energy beam created by ionizing an inert gas. First the material is heated locally with a gas flame. A narrow stream of oxygen causes the metal to oxidize, and at the same time blows away the molten oxide and metal.

The metal can also be cut with a nibbling machine – an electrically powered machine that pinches off small bits of metal at a time. A portable nibbling machine can cut about a meter per minute in three to five-millimeter thick steel. The heat created in the cut surface is negligible; but a fairly large opening is needed to get the equipment into place and start working.

But how do you get through the insulation? A classic method of getting into a safe or vault is to use explosives. This method has many disadvantages; it may be successful on older safes, but the contents may be damaged. Safe-crackers can use what are known as jam shots to blow off the safe’s doors.