Most master locksmiths knew how money chests were made; such knowledge was part of their education. According to one narrative to the Stockholm magistrate in 1774, “Nowadays there are many useful masterpieces in the work setting, such as an iron chest with 16 to 24 bolts in a lock, a church door lock, or a well-made port lock, a large cash box or chest lock even with deepened chest.”

The rolled plates for sides, bottom and lid were chiseled out and later cut to the right size. Then holes were made for strips, edging, handles, hinges and shackles. On the side plates the bent intersecting strips were riveted, leaving room for the edging that frames the chest. The plates were then aligned. The sides and bottom were riveted in place using edging along the corners. The lid was fitted with lock and hinge.

|

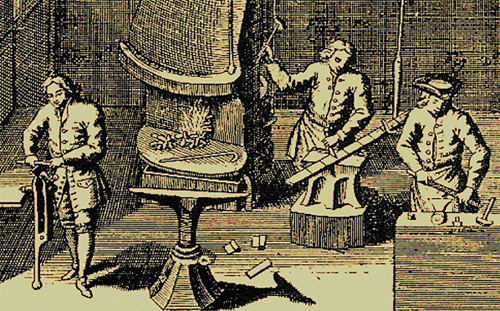

| Locksmith in the middle of the eighteenth century, working with file and chisel. According to Duhamel du Monceau, Art du serrurier, Description des arts et métiers, printed in Paris 1767 |

The master had journeymen to help him. Guild members were divided into three distinct levels: master, journeyman and apprentice. Everyone began as an apprentice and after several years could rise to the level of journeymen and finally, after a test, could achieve the level of master craftsman. Only the masters had the right to independently exercise a craft.

Each craft guild included craftsmen with a monopoly in specific trades and therefore controlled production and quality. The organization was defined by a common international regulatory framework, the guild statutes. In many cases the smiths were paid via the previously mentioned putting-out system. Guilds in Sweden were abolished in 1846 after being discussed in Riksdag session after Riksdag session since the early nineteenth century. Freedom of trade was not implemented until 1864. The implication was that “All men and women of legal age have been granted the right to support themselves through any occupation at all.”

It was first at this time, in the 1850s, that the mechanical equipment was sophisticated enough for industrial manufacturing of locks in Sweden to be discussed.

|

| Still in the bank environment. Money chest in Nordeabanken in Jönköping. Front, back and detail of the lid over the keyhole. The chest has been repainted. Photo by the author. |

A certain standard

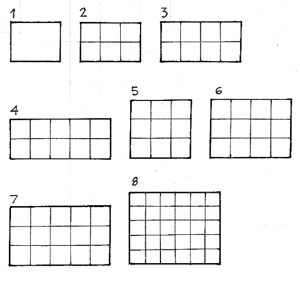

I have investigated whether there is any common standard in the production of nineteenth century money chests.

The different producers appear to agree that the chests must be made of rolled sheet iron, have intersecting iron strips, and be painted green with black fittings. The keyhole is positioned centrally on the top of the lid, the chest requires double hinges and handles, and the chest must have single or double padlock fittings.

However, the sizes vary, the number of intersecting strips varies, the placement of the smaller four-sided lock under the lid varies, and there are at least a few variations with respect to both placement and type of lock. Whether or not the chests are insulated is another variation.

|

| Diagram showing commonly found fronts on nineteenth century money chests. Numbers 6 and 7 are the most common. Diagrams by the author. |